This article serves as a summary of my work as well as an explanation of the importance of evidence produced and that should be produced by the field of virology.

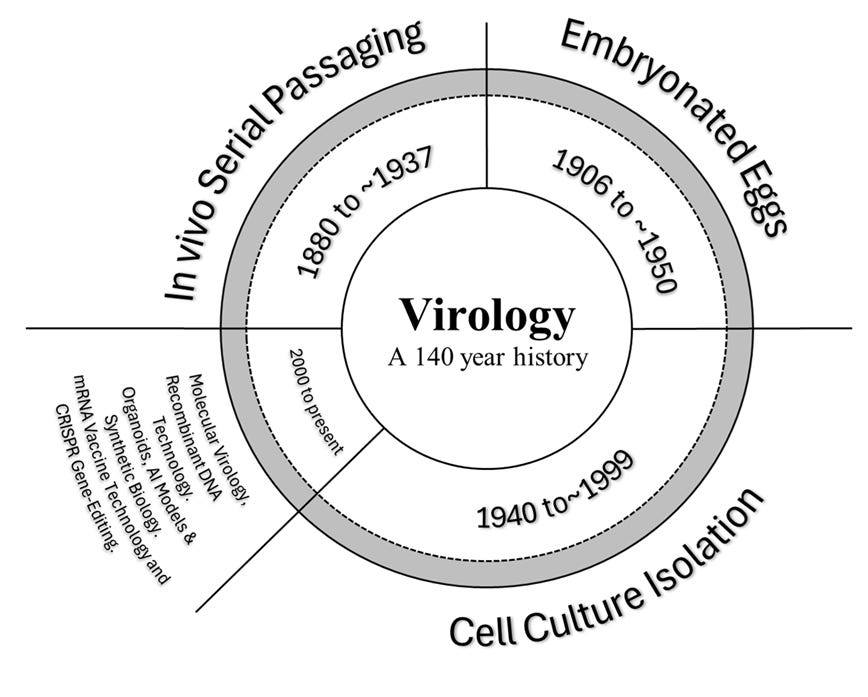

The historical progression of dominant isolation methods in virology over the past 140 years can be categorized into distinct periods, each characterized by the prevalence of a particular technique. These methods, as illustrated in the accompanying image (see below), reflect the evolving approaches within the field. However, it is important to note that none of these methodologies have been able to directly detect a virus. My previous research provides a critical analysis of the methods as follows:

Reassessing the Foundations of Virology: A Critical Look at Historical Methods for:

In Vivo Serial Passaging.

Embryonated Eggs.

Briefly Touched on Modern Techniques Post 2000.

Reevaluating Viral Transmission: A Critical Examination of Virological Methods and Assumptions for cell culture isolation.

It is essential to emphasize that these methodological challenges are secondary to a more fundamental issue within the field of virology. Over the same historical period, no study has conclusively demonstrated that a diseased host can transmit the disease to a healthy host through natural transmission routes. In the absence of such definitive evidence, virology faces significant difficulties in substantiating its definition of what constitutes a virus. The prevailing definition describes a virus as:

An infectious, obligate intracellular parasite comprising genetic material (DNA or RNA) surrounded by a protein coat, and sometimes an additional lipid envelope, that relies on a host cell's machinery for replication.

Infectiousness is regarded as a defining characteristic, distinguishing functional viruses from particles incapable of completing the replication cycle. For a more in-depth exploration of this issue, refer to my paper titled: Reevaluating Viral Transmission: A Critical Examination of Virological Methods and Assumptions.

If the significance of evidence for transmission and isolation were to be represented visually, it could resemble two stacked pie charts, as depicted in the image below. Without definitive proof of infectiousness (i.e., transmission), the existence of a virus cannot be conclusively established.

Furthermore, despite the absence of such proof, we can take the analysis a step further by examining isolation methods. Nearly 80% of the evidence within the field relies on the cell culture isolation method, while the remaining 20% consists of other techniques. However, even this distinction is somewhat misleading, as most—if not all—of these alternative methods ultimately depend on cell culture isolation or are derived from data obtained through this process. Therefore, virology does not just fail to provide conclusive evidence of infectiousness but it also fails to provide conclusive evidence in the form of isolation due to the inconsistencies and shortcomings I have laid out in my paper.

The data can be further visualized by comparing the relevance of different types of evidence against the volume of research produced in virology. The most critical form of evidence would be definitive proof that a diseased host can transmit an infection to a healthy host through natural means. This should be represented as having the most relevance (or ~100%), as without clear proof of infectiousness, claims of isolation hold little significance. However, what we see in virology is a disproportionate focus on producing evidence that aligns with existing methodologies rather than prioritizing the most fundamental questions. This is illustrated in the graph below, where the blue bars represents the importance of different types of evidence (infectiousness being the most important), while the red bars reflects the quantity of research produced for the different types of evidence. When considering the quantity of research, the minimal proportion allocated to infectiousness merely represents an attempt to provide supporting evidence—yet, as I have demonstrated in my previous work, no conclusive evidence exists.

Based on the above assessment I list my papers and articles in the order of importance as follows:

Excellent work, Matthew.

While taking no active position on the existence or otherwise of viruses, I have an acute distrust of the Medical Mafia and I have witnessed its indifference to human values at first hand and have even been the intended victim of an attempt to medically kill a troublesome denier of 'vaccine safety and effectiveness'. Thus, I am very receptive to more logical causes of ill-health. Incidentally, I have no medical knowledge or skills.

My attitude does not entirely reflect a spirit of rebellion. For almost three decades now I have avoided colds and flu by adoption of one single technique: every day I consume an inch-wide slice of red capsicum. Not green or yellow, but red. Occasionally, I have been in situations where this is inaccessible and, if there is a flu-sufferer in my immediate vicinity I feel the old familiar tickle in the nasal region and throat. A saline flush can buy me time but within 24 hours of ingesting my red supply, I am back to full health again. I mention this because the usual glib conclusions do not apply. This preventive remedy, now copied by others, works 100%. Nothing I have been told about viruses suggests red capsicum is a virus killer but principles of nutrition tell me there is a component of red capsicum that prevents an ear/nose/throat condition and this is completely unresearched. I suspect that out of such research the actual culprit, almost certainly not a virus, might finally be identified. Anyway, thanks Mathew. This is a war you will eventually win.